This spring saw the largest single urban forest carbon credit purchase in U.S. history. Through a deal that reportedly bought out all available city forest credits, a group of 13 government entities and other organizations with urban forestry projects collectively earned more than $1 million – revenue that can go back to supporting tree planting and management programs.

Market participants say the rising price of urban forest carbon credits signals buyers increasingly recognize the extra benefits to city dwellers that come with protecting these forests. They also say limited awareness of urban forests and their ability to offer credits, a lack of binding requirements to participate, and local governments’ minimal capacity to propagate such programs could slow growth.

A carbon credit is a purchasable permit representing carbon dioxide (or an equivalent of greenhouse gases) removed from the atmosphere, such that a buyer might compensate for or neutralize their own environmental impacts. While forestry-related credits are among the more common options available, they’ve also been criticized for enabling companies to greenwash without lowering overall greenhouse gases levels.

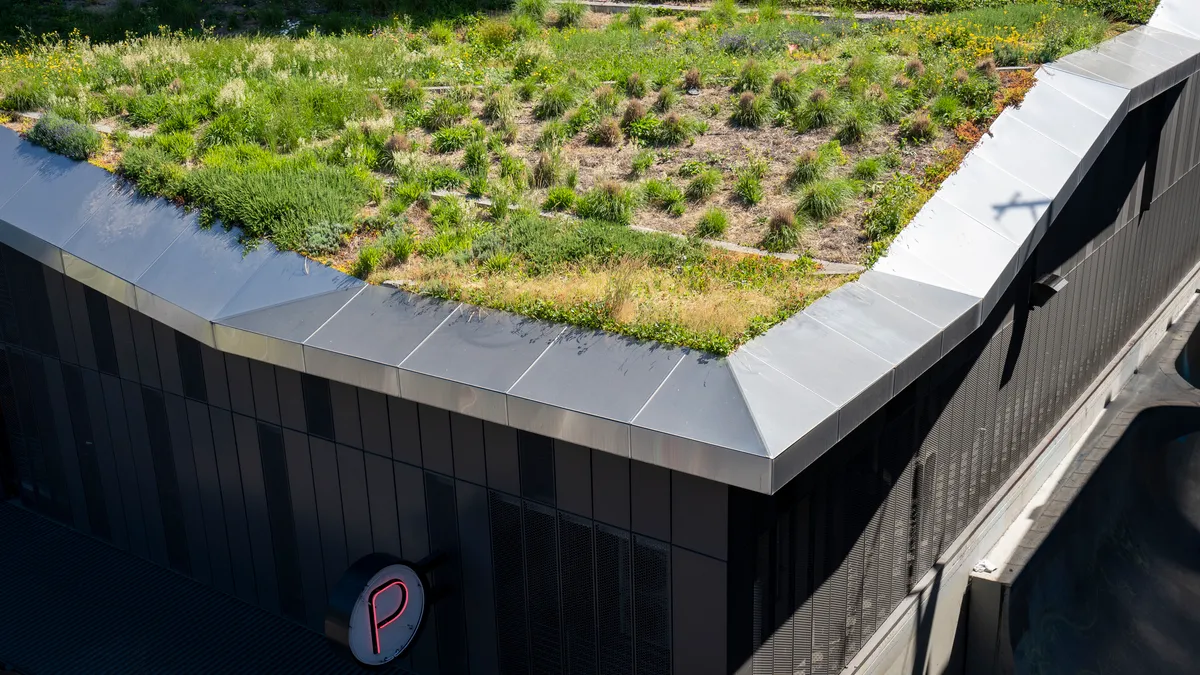

Urban forest carbon credits, on the other hand, are more novel. Supporters say their benefits offer a new kind of value that goes beyond just the protection of trees by also improving community air quality and people’s mental health.

A fraction of the earnings in the million-dollar deal this spring went to King County, home to Seattle. One of the most notable aspects of the deal was the high price that the credits garnered, said Kathleen Farley Wolf, who manages the King County Forest Carbon Program. According to a press release from the buyer, Regen Network — a full-stack blockchain software development company that seeks to support ecological regeneration — the price per credit was between $34 and $45 per metric ton of carbon, compared with 2020 published pricing for global forest carbon credits between $2 and $10 per credit.

“That price is really a signal that these kinds of projects are highly valued and that there's recognition that doing urban forest projects is expensive; cities are expensive, suburbs are expensive. We're in a particularly expensive area here in King County,” Farley Wolf said.

There’s growing demand for these credits amid a surge in corporate net-zero commitments, according to Liz Johnston, the director of City Forest Credits, a registry organization founded in 2015 that manages and promotes urban forest carbon credits.

Still, one limitation to marketing urban forest carbon credits is simply that the acreage of urban forests is less than that of other forests. Entities interested in making such carbon credits available also require some sort of local program implementer, but certain municipal governments may lack the administrative capacity to support that role, according to Molly Henry, director of climate and health at the national nonprofit American Forests.

To bridge that gap, American Forests is in the early stages of working with the city of Providence, Rhode Island, to serve as that local implementer. Particularly for local governments that were going to plant trees anyway, “that's nice to have that extra revenue source, and it's not huge, but it's enough that it can maybe take a little bit of a load off of the pressure that they have in their budget,” Henry said.

Moving forward, locally recognized benefits from urban forests could also be one catalyst for justifying such investments. “The narrative is so much more compelling because of the way that we can quantify the health benefits for the people that actually live there directly in the community,” Henry said, adding that pressing issues like extreme heat and poor air quality “are going to only make it more relevant.” Henry also noted that some carbon credits now are focused on not just removing carbon from the atmosphere, but are coupled with other benefits unique to urban trees compared with those in a natural forested landscape.

Farley Wolf also said King County has sought to generate interest among local buyers specifically interested in protecting local forests.

For now, participation in carbon credit marketplaces remains voluntary. But further commitments from companies or municipalities, or binding government regulations and policies, would transform the market, Henry said.

Awareness about urban forest opportunities also still needs to build, Henry noted. “They're a fairly young organization and they're doing a very new thing,” Henry said regarding City Forest Credits. “I don't think the first thing that buyers think of is investing in urban forests, and I don't know that ‘urban forest’ is even part of the vernacular of most people.”