Dive Brief:

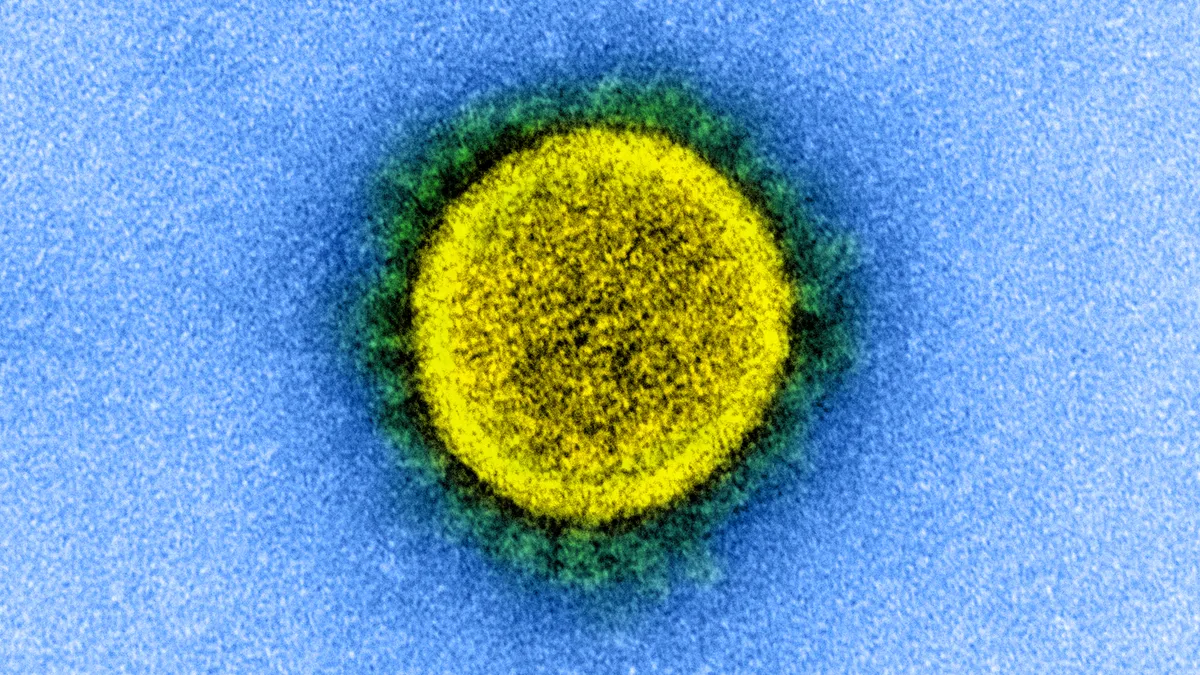

- A pilot project in the City of Ashkelon, Israel, has found that the coronavirus (COVID-19) can be detected in wastewater much quicker than through testing people, while places of infection can be pinpointed to specific neighborhoods or streets.

- Led by wastewater management technology company Kando with partners from Israeli academic institutions including Ben Gurion University in Beersheba and the Technion in Haifa, researchers found late last month that there were many more traces of the coronavirus present in wastewater and sewage, even though the city of 150,000 people is generally regarded as having a low number of cases. Kando took samples and used sensors and other technology to measure the concentrations of virus remnants and determine an approximate number of positive cases.

- That detection has two benefits, according to Yaniv Shoshan, Kando's vice president of product. It means cities can pinpoint specific areas to lock down based on infection rates rather than shut down entire communities. And it is a much quicker way to detect cases than by testing people, as tests can take too long to return, or people can be asymptomatic and spreading the infection without realizing, Shoshan said.

Dive Insight:

Research on using wastewater to detect coronavirus cases has accelerated in recent times, having been experimented with by the likes of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute and the University of North Carolina's Institute of Marine Sciences, among others. Massachusetts-based Biobot Analytics announced in early April its technology would be applied to analyzing sewage for traces of COVID-19, and it has partnered with 400 cities in 42 states on its sewage testing program.

For the United States, which is still struggling with a testing regimen that lags many other countries and fails to deliver timely results, Shoshan said using wastewater as a way to detect the infection could be far more effective as it produces quicker results.

He noted that it could take two weeks or more from someone realizing they have symptoms to getting a test to receiving their results, during which time they could have been spreading the virus. "Two weeks is a lot," Shoshan said. "Two weeks is stopping it when it's small or fighting it when it's a monster."

The original goal of the study was to show that the technology could be used to detect coronavirus in a specific building, with the city's "coronavirus hotels" that house patients used as a proving ground. But while Shoshan said local officials thought the coastal city was "totally clean" otherwise, that was not the case as there were significant remnants of COVID-19 in wastewater.

For cities grappling with the need to either continue citywide lockdowns or do them on a more localized basis, Shoshan said detecting coronavirus in wastewater can enable local officials to make more granular decisions about lockdowns and so have a smaller economic impact.

Especially with testing not doing a good enough job, detection by other means might be better to help prevent the spread, he said. "I think every city should have this kind of alert system, intelligent system, that can reduce the risk of economic problems because of coronavirus," Shoshan said.