Electrifying and decarbonizing one home is a step in the right direction. But what if a whole neighborhood had cleaner, more efficient power?

Paulo Cesar Tabares-Velasco, an associate professor of mechanical engineering with the Colorado School of Mines, wanted to find out. His question has led to 16 manufactured-home owners in Lake County, Colorado, agreeing to swap out some gas-powered appliances for electric ones, increase their insulation, make small retrofits and subscribe to a community solar installation elsewhere in the state. The project is partially funded by federal grants and includes partnerships with state agencies, other researchers, the local utility and others.

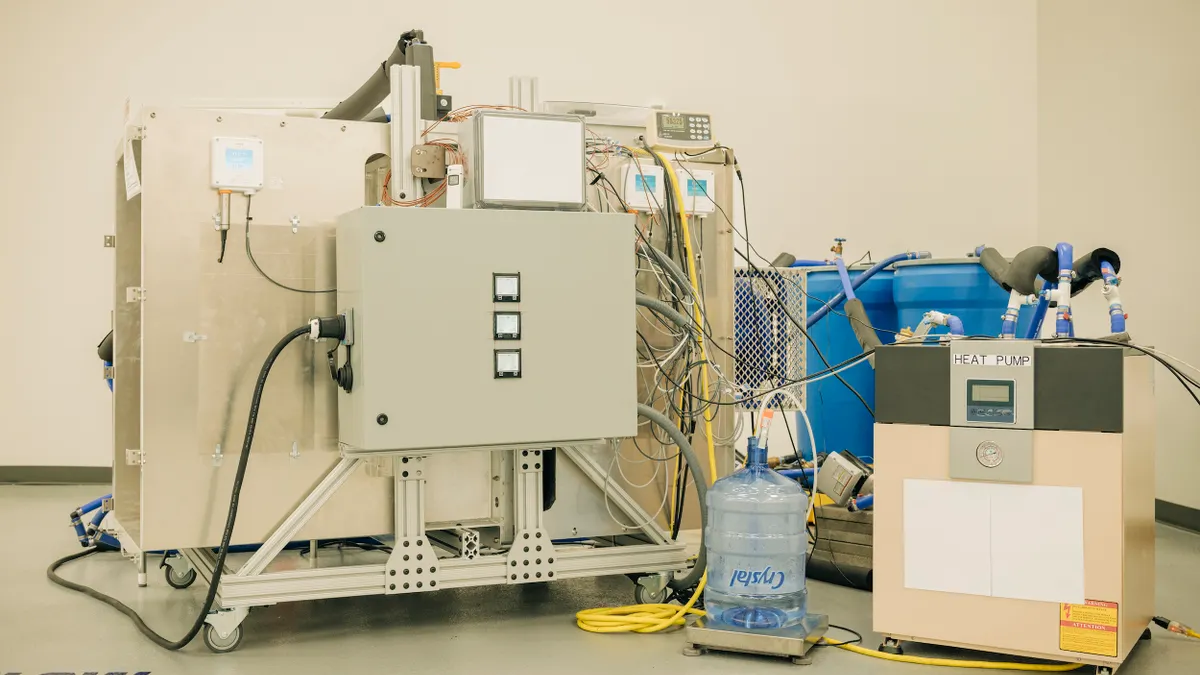

Tabares-Velasco says the project is among the first community-scale decarbonization and retrofit projects in the U.S. In the coming months, each home will get an electric heat pump and battery. Retrofits that wrapped up this fall include new insulation, LED lighting upgrades and the installation of high-efficiency furnaces (which will serve as backup equipment in case the heat pumps ever fail). The goal is to make the homes more reliant on electricity while ensuring residents’ energy bills drop, a challenge for their cold conditions at 10,000 feet above sea level.

“If we can fix it here, we can fix it everywhere else,” Tabares-Velasco said. It’s a promise participants think can be delivered on, despite the financing and logistical struggles that often come with renovating manufactured housing.

The power of ownership

Making up about 6% of the housing stock in the U.S., manufactured homes — formerly known as mobile homes — are notoriously energy-intensive per square foot. Residents of manufactured homes also report the highest levels of energy insecurity on several metrics, such as cutting back on food or medication to meet power bills. When Tabares-Velasco and his colleagues brought the idea of this program to the manufactured home community in Lake County, the appeal of lower energy costs drew people in, he said, along with the prospect of improvements that would make parts of the homes last longer.

Analy Gurrola, one of the homeowners participating in the renovations, was interested in the project as soon as she heard about it, even though she had already completed some renovations the project might have covered.

Unlike manufactured home communities nearby, which sit on rented land, Gurrola and her neighbors own the land they live on, a crucial factor for the program’s success, according to Tabares-Velasco. Tabares-Velasco worried that bringing retrofits to homes on investor-owned or privately held property was too risky since a drastic rent change could force the participants out. Plus, cooperative status means the homeowners are already skilled at working together, he said.

Manufactured home communities face distinct barriers to accessing funding for energy efficiency improvements compared with more traditional housing types. State laws classify most manufactured homes as chattel property, the same as cars and boats. If lenders even offer chattel loans, the interest is high and the terms are short, a tough ask for homeowners with a median annual income that is less than half that of those owning traditional single-family homes. In traditional single-family housing, large renovations or repairs are often funded through home equity loans, something most owners of manufactured homes can’t access.

In cooperatives like Gurrola’s, which represent about 2% of manufactured home communities in the U.S., homeowners control an organization that owns the property their homes stand on, or they are shareholders in the land, creating a different relationship with banks. Research in New Hampshire — the first state with a resident-owned manufactured housing group — shows that cooperatives offer residents a chance to build equity. Lending organizations in New Hampshire also offer traditional mortgages to manufactured home owners who own their land or are part of co-ops.

Paying for retrofits

Once community members in Lake County agreed to participate in the decarbonization effort, the project leaders had to see which residents were eligible for the first wave of construction. Insulation and other energy efficiency measures were paid for by the federal Weatherization Assistance Program, or WAP, which helps lower-income families with smaller renovations. Some residents declined to participate for various reasons, Tabares-Velasco said. The WAP application is long and asks for personal details, from citizenship and immigration status to financial records.

Every individual homeowner in the community had to apply for WAP funding, but the rules differ for multifamily housing. There, every unit can receive weatherization if only two thirds (or in rare cases, just half) of the building meets the income requirements. Tabares-Velasco thinks a similar policy for manufactured housing communities could allow more residents to access the funds.

Any home, manufactured or not, has to meet more than income requirements to access WAP funding: The program denies aid to construction deemed beyond repair or structurally unsound. If there is too much asbestos or if “a major portion of the total electrical system appears to be questionable,” units can be turned away, too.

Older manufactured homes can be prone to the kinds of repairs that WAP requires before offering funding. About 20% to 30% of manufactured homes nationwide were built before the first federal construction standards for the housing type went into effect in 1976, says Dave Anderson, the executive director of the National Manufactured Home Owners Association, a nonprofit that advocates for manufactured housing rights. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development made those rules because some models were so poorly made, he said. “I don’t think anyone imagined that almost 50 years down the line, pre-HUD [manufactured homes] wouldn’t be phased out,” Anderson said.

If loans are hard to access and manufactured home purchasers buy in cash — which they do three times more often than those pursuing site-built homes — the most budget-friendly option is often the oldest. Even if these older homes don’t need additional work, the way they are built can hinder some weatherization measures. For example, early designs often used a smaller lumber variety that doesn’t leave enough space in the walls for added insulation, Anderson said.

About a third of the homes in the Colorado cooperative Tabares-Velasco is working with were built before the federal standard; the newest is from 2000. To avoid promising repairs that would later be denied, Tabares-Velasco and his team surveyed the units before the WAP application process began. Ultimately, 14 of the 28 homes in the cooperative chose to participate and received WAP funding. Two more on nearby properties also joined in.

Hurdles to decarbonization

Some project challenges mirror those of other electrification efforts in the U.S. The manufactured homes might need higher-capacity electric panels capable of supporting the increased draw on electric power. The local utility for the Colorado manufactured home community looked into whether it needed to upgrade a nearby transformer, a piece of equipment that converts high-voltage electricity from the grid to lower voltage that can safely be used in homes. The investigation has taken months and expanded into questions about other potentially necessary utility equipment changes, Tabares-Velasco said.

Tabares-Velasco is skeptical that the upgrade is needed: Simulations suggest the existing transformer could handle the load. Plus, the homes will have smart controls and batteries on site. His team will explore the question of whether more utility equipment upgrades are needed to support the electrification effort as data comes in.

Other decarbonization hurdles are distinct to manufactured homes. Some energy-efficient appliances didn’t physically fit in the layouts, Tabares-Velasco said. Some water heater closets only allowed 18-inch-diameter tanks, but all the heat pump-based water heater models the team could find were at least 20 inches across. The project team ditched its original plans in favor of standard electric water heaters instead, in part because data collection for research is easier when the equipment across the homes is the same.

One of the other partners in the project is also paying attention to how installations progress. The Colorado Energy Office administers WAP funding and helped secure U.S. Department of Energy grants to cover the rest of the work. The state agency hopes the project can offer lessons on whether household renovations are more effective at a neighborhood scale instead of one-by-one, said Michelle Butler, senior engagement manager for the office. She and her colleagues are taking note of which appliances or supplies work for manufactured homes and why.

The Colorado Energy Office is also tracking the cost of bulk buys of heat pumps and other high-efficiency or electric appliances.

Looking ahead

More construction needs to happen before the project can offer full feedback on lessons learned.

Among the project team’s remaining work is getting residents a subscription to an Xcel Energy community solar garden elsewhere in the state. The subscription will credit homeowners on their energy bills for the amount of electricity generated that goes into the grid. The connection will be free for the residents in Lake County and is key for delivering lower energy costs, since switching from natural gas to electricity can sometimes result in higher energy bills for customers in Colorado, Butler said.

Looking ahead, Anderson from the manufactured housing rights nonprofit is eager for wide-scale financing changes. Federal legislation passed in 2008 required Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to offer better lending options to three types of housing, including manufactured units, but implementation has been slow.

Meanwhile, Gurrola and her neighbors are heading into the first winter with newly weatherized homes and soon, heat pump heating. Trust and effort are involved in letting work teams into homes or allowing researchers to collect data, Gurrola said. But it didn’t take long before residents who opted out started asking if they could change their minds, she added.

“I’m just excited for the process to keep moving forward and see how it all works out,” Gurrola said.