A pedestrian in Memphis, Tennessee, is nearly 17 times more likely to die in a traffic crash than one in Boston. The 2022 death rate for pedestrians in the Home of the Blues was 13.5 per 100,000 people, while Boston’s was 0.77.

Nine of the 10 most dangerous states for pedestrians are in the Sun Belt, according to a 2022 Smart Growth America report. The populations of Sun Belt metropolitan areas are increasing faster than those in the rest of the country, according to a 2020 study from the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University. In these “auto-oriented” cities, low-income populations also are growing faster than in the rest of the nation, and low-income neighborhoods “are located in inconvenient places far from jobs and hard to serve with transit,” the report says.

Sun Belt cities tend to have higher pedestrian fatality rates

Southern cities that lack adequate public transit experience higher overall traffic fatality rates, according to an Eno Center for Transportation analysis. Average traffic speeds in many of these Sun Belt cities are higher than the speeds in Northern cities such as Boston, Chicago or Seattle, per an analysis by Streetlight Data.

“There's this confluence of social trends that are all negative for pedestrian safety,” said Angie Schmitt, author of “Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America” and the founder of a consulting firm focused on pedestrian safety. “People are moving to places that are a little more dangerous,” she said.

But these cities are not unaware of the crisis on their streets. Here’s how three Sun Belt cities are taking steps to level the playing field for pedestrian road users.

Tucson dedicates $150 million to street safety

Tucson, Arizona, is one of the booming Sun Belt cities. It has seen its population grow 30% from 1990 to 2021, and nearly 20% of its residents live below the poverty line. Nearly three-quarters of commuters drive alone to work, while just 5% walk or bike, and 3.4% rely on public transit.

Nearly 50 pedestrians lost their lives last year in Tucson, according to Smart Cities Dive’s analysis. In May 2022, voters approved the 10-year extension of a half-cent sales tax for street improvements, with $150 million “dedicated to safe street improvements that benefit all users and modes … such as street lighting, sidewalks, bicycle network enhancements, traffic signal technology upgrades, and traffic-calming features,” according to a project website. In June the city designated and began scheduling three phases of work.

“A couple of years ago, we were in the low 20s [in pedestrian fatalities], so the number has just skyrocketed,” said Patrick Hartley, Complete Streets program coordinator for the Tucson Department of Transportation and Mobility. Tucson’s 2022 pedestrian death rate was 8.96 per 100,000 population, second worst after Memphis among cities with at least half a million population.

Asked about the causes for the increase in pedestrian deaths, Hartley described a “toxic cocktail” that includes speeding on city streets, higher-speed roads lacking enough pedestrian crossings, poor street lighting and substance abuse by pedestrians. A 2022 analysis by the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office found that of the 72 pedestrian deaths in the county in which Tucson is located, 71% of the victims underwent toxicology screening, and more than three-quarters tested positive for methamphetamine, fentanyl or other substances.

Tucson’s new funding comes in the wake of several other projects to improve street safety. It installed more than 90 high-intensity activated crosswalk, or HAWK, signals that, when activated by a pedestrian or bicyclist, warn drivers to stop. Hartley said they’ve been “extremely effective” but are expensive. The per-unit cost runs to $100,000 compared with a few thousand dollars for a marked crosswalk or up to about $30,000 for a raised crosswalk. Another project involves upgrading permissive left-turn signals to turn red when a pedestrian pushes a button to cross the perpendicular street.

Most important, said Hartley, has been a change in attitude. “Historically, we were in a road-widening phase,” he said, “but we've put a stop on that recently.” The city is now looking to introduce “road diets” with bikeways and safer crossings, thus reducing and slowing traffic for a “better pedestrian experience on those roadways as well as reducing vehicular crashes,” Hartley said. In February, the U.S. Department of Transportation awarded Tucson’s Pima County $1.5 million under the Safe Streets and Roads for All program to create an action plan to improve road safety.

Jacksonville addresses ‘areas of persistent poverty’

Jacksonville, Florida, is a rapidly growing city with “a very car-centric environment,” said Greer Gillis, senior vice president and chief infrastructure and development officer for the Jacksonville Transportation Authority. Jacksonville’s poverty rate is nearly 15%, according to the latest Census Bureau numbers.

Gillis said areas of persistent poverty are “where the hot spots are for bicyclist and pedestrian crashes and fatalities.” She cited a lack of sidewalks, poor lighting at intersections and crosswalks, and crosswalks that are too far from bus stops.

The JTA is working with the city of Jacksonville, the North Florida Transportation Planning Organization and the Florida Department of Transportation to focus road construction more on people and less on automobiles as they build additional roadways, Gillis said. Some of that involves construction along high transit-ridership corridors, Gillis said, where those riders may not have a convenient sidewalk or crosswalk to safely reach a bus stop.

One such project gave residents in the McDuff Avenue and Fifth Street neighborhood new sidewalks on both sides of those streets as well as bike lanes. “The residents have already said it's a marked improvement because now they can walk outside of their homes and just come right to our bus stop,” said Gillis.

Los Angeles lowers speed limits

On the West Coast, Los Angeles saw pedestrian deaths within the city jump more than 21% between 2020 and last year, from 124 to 152. The city’s pedestrian death rate in 2022 was 3.98 per 100,000 people. It was a particularly deadly year for traffic fatalities, said Colin Sweeney, director of public information at the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, in an email.

“Sadly, traffic violence disproportionately impacts the most vulnerable — kids, seniors, and the unhoused in communities of color already burdened with higher rates of poverty,” Sweeney said.

Speed is correlated with risk of death for pedestrians

The deaths continue: On Oct. 17, a driver accused by prosecutors of zooming along at 104 mph lost control of his car and killed four women — all college seniors — as they walked along Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu, California, where the speed limit is 45 mph. Malibu is within Los Angeles County.

For Los Angeles County, the Department of Public Works oversees transportation, including roads, sidewalks, bike lanes and other infrastructure. Matthew Dubiel, principal engineer with the DPW, explained that its jurisdiction covers a wide variety of unincorporated urban, suburban and rural communities. Thus, “it's not one-size-fits-all in terms of the solutions that we need to bring to the table,” he said.

Half of all fatal and severe-injury collisions on county-maintained roadways take place on just 4% of those roads, Dubiel said. “Speed is a factor” in the number and severity of collisions in all areas, he said.

In the county’s more urbanized communities, DPW is implementing tactics to improve pedestrian safety that include curb extensions to slow vehicles making right turns, high-visibility crosswalks and traffic signals that give pedestrians extra time, Dubiel said, adding that these projects “can really begin to move the needle at a large population level.”

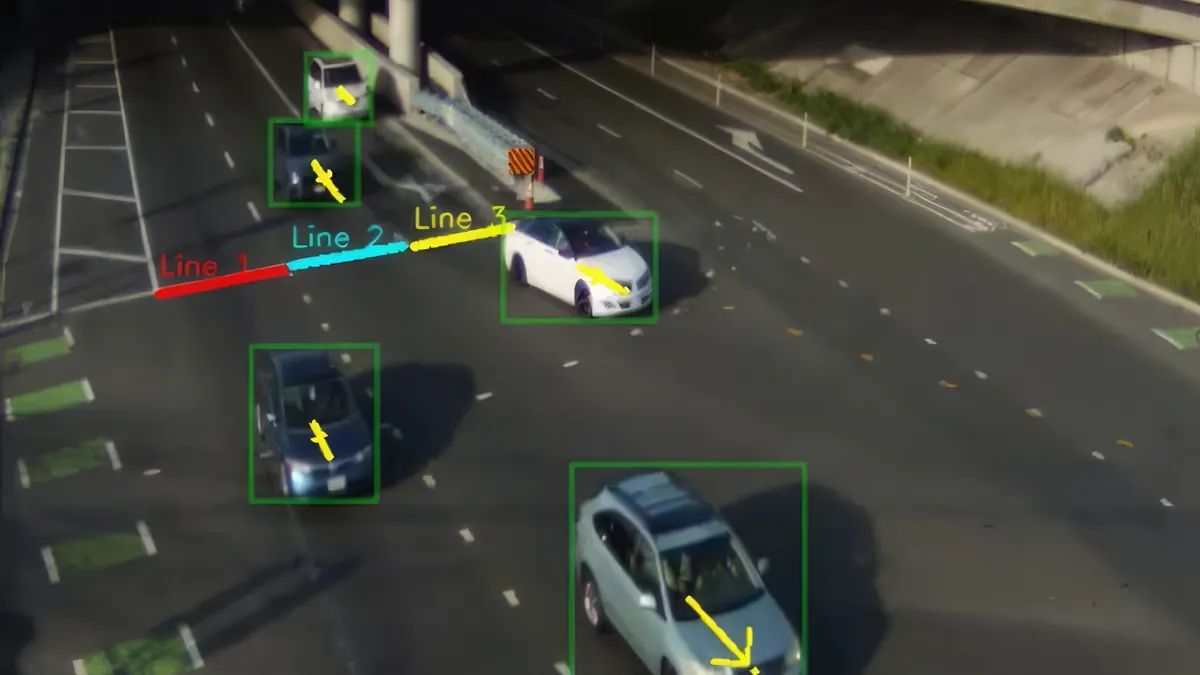

LA DOT reduced speed limits on 177 miles of Los Angeles streets in 2022, thanks to a new state law that changed the California Vehicle Code to give cities greater flexibility to set safer speed limits on their streets. As of April 2022, LA also made traffic signal timing changes at more than 800 locations to give pedestrians more time to cross the street, which reduced pedestrian crashes by up to 33%, and installed 79 flashing beacons at crosswalks, which decreased pedestrian collisions by 50% at those locations, according to LA DOT.

“LADOT is confronting this urgent public health crisis by putting people at the center of all decision-making, reversing a history of putting vehicle speeds and volumes first,” Sweeney said.

Many more communities, large and small, are working to make their streets safer for pedestrians. America Walks, a nonprofit focused on walkable communities, highlights efforts in Durham, North Carolina; Indianapolis; and Boise, Idaho. Other cities, including Nashville, Tennessee, are upgrading crosswalks, eliminating right turns on red and creating bike and pedestrian pathways.