While the nation focused on Flint, MI's water crisis in 2014, another crisis was unfolding to less fanfare in Toledo, OH.

A harmful algal bloom in Lake Erie, which supplies Toledo's drinking water, had entered the city's water systems. On Aug. 2 of that year, residents received an urgent warning not to drink or use their tap water — an order that was in place for nearly three days.

A renewed focus on water quality emerged out of that crisis, leading to the creation of Smart Lake Erie. The project, led by the nonprofit Cleveland Water Alliance (CWA) and various partners, has echoes of the Jefferson Project at Lake George in New York.

Smart lake initiatives are gathering momentum as more cities and water groups look to improve drinking water quality and ultimately avoid another public health crisis.

Algae, salt erode water quality

Harmful algal blooms, which release toxins into the water and contaminate the supply, are a major issue that smart lake technology looks to solve. The blooms occur when algae grows out of control, although the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said it is unclear how various factors come together to produce the harmful blooms.

A combination of pollution, changes to water flow and climate change may all play a role, as well as nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen flowing into the water from lawns and agriculture, according to NOAA. And the effects can be devastating.

"This is a really big disruption to fish habitat and other aquatic plants and animals every single summer," Max Herzog, program manager for Smart Lake Erie at CWA, told Smart Cities Dive in an interview. "And it also has really significant impact on the regional economy, particularly around tourism and recreation as well as property values."

The human cost can be tremendous, too. In a video produced by the Ocean Conservancy on preventing water crises in the Great Lakes, Scott Moegling, water quality manager for the City of Cleveland, recalled in 2006 when lake algae got into the city's water treatment plants and residents' pipes in 2006. The drinking water was yellow and the system needed flushing to remove the harmful algae.

Outside organizations are similarly worried about the effects of harmful algal blooms on water quality. In an interagency report prepared for the White House by the National Science and Technology Council in August 2017, scientists from a slew of federal departments warned the impacts can be tremendous for the everyday existence of wildlife and humans.

"They also can have serious effects on a community’s social health, causing lost revenue for lakefront economies that are dependent on aquatic or seafood harvests or tourism; disruption of subsistence, social, and cultural practices; or loss of community identity tied to aquatic resource use," the report reads. "These impacts cause us to ask critical questions: Is it safe to drink or bathe in my tap water? Can we swim at the beach? Can I eat this fish? Are my pets at risk? How will this affect my business or job?"

Lake George in upstate New York is not as troubled by harmful algal blooms, though advocates and others say they closely monitor the situation. Instead, a major concern is the infiltration of salt into the water from trucks salting roads to prevent icy conditions. As the area grew with new construction and roads, the salt runoff has only intensified and can be toxic to wildlife while degrading water quality.

"Road salt is one of the most serious threats to the water we face," Eric Siy, executive director of advocacy group FUND for Lake George, told Smart Cities Dive. "And it's been largely overlooked and ignored for way too long, and it's now catching up to us in very ugly, insidious ways."

Nearby septic systems from the houses around the lake can also cause issues if they are not properly maintained, leading to contamination, Siy said.

"Road salt is one of the most serious threats to the water we face. And it's been largely overlooked and ignored for way too long, and it's now catching up to us in very ugly, insidious ways."

Eric Siy

Executive Director, FUND for Lake George

The desire to avoid drinking water crises has become such a concern for elected officials in Ohio and New York that it prompted statewide plans. Ohio recently launched H2Ohio, which invested $172 million over its first two years in data-driven solutions to prevent harmful algal blooms and phosphorus runoff.

At the unveiling of H2Ohio, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, R, said the science-based plan will protect water quality while also investing to help farmers and other sectors change their habits.

"Quite simply, our state can't flourish if we lurch from water crisis to water crisis," DeWine said.

And New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, D, in 2018 announced action plans to combat harmful algal blooms in 12 lakes as part of a $65 million initiative to protect upstate water quality.

Tech-driven monitoring

To fight the major problems of harmful algal blooms and contamination in salt and septic systems, Lakes Erie and George are turning to technology, including intricate sensor networks, to monitor their water quality.

On Lake George, the Jefferson Project began in 2013 as a partnership between IBM, the FUND for Lake George and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), with the latter already conducting research at its Darrin Fresh Water Institute located on the lake.

The Jefferson Project deployed more than 500 sensors throughout Lake George on 52 intelligent sensor platforms that provide real-time data on various conditions, such as currents. The lake also has floating robotic buoys with sensors that can be lowered to various depths to measure the water temperature, its acidity on the pH scale and levels of chlorophyll. The buoys have full weather stations to capture wind speeds and monitor conditions in the air to provide insights on the effects of inclement weather.

Harry Kolar, an IBM fellow and associate director of the Jefferson Project, told Smart Cities Dive some weather stations have also been built on rock outcroppings in and around the lake. There are also stations in the lake’s tributaries measuring the flow and depth of the water, as well as salt levels and the chemistry of the water flowing into and out of Lake George.

They then communicate with each other using artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and internet of things (IoT) technologies to feed data into the Jefferson Project’s modeling.

These investments were triggered by a 30-year study of the lake's water quality, which collated data on various trends including the runoff of road salt. Siy said the technology-driven approach represents a sea change from previous water quality monitoring efforts at Lake George, which he said were part of a "piecemeal" approach that focused more on reacting to issues as they came up.

"We really turned the status quo on its head and determined that we know what's happened over the past generation to Lake George, under the status quo approach to protection ... [W]hat do we want the next generation of Lake George to look like?" Siy said. "Well, if we want to change the trend lines, we have to evolve from the status quo."

It is a similar story at Smart Lake Erie, which spun out of a series of Erie Hack innovation challenges hosted by CWA and its partners. In its first edition in 2017, a lot of focus was on real-time water quality monitoring.

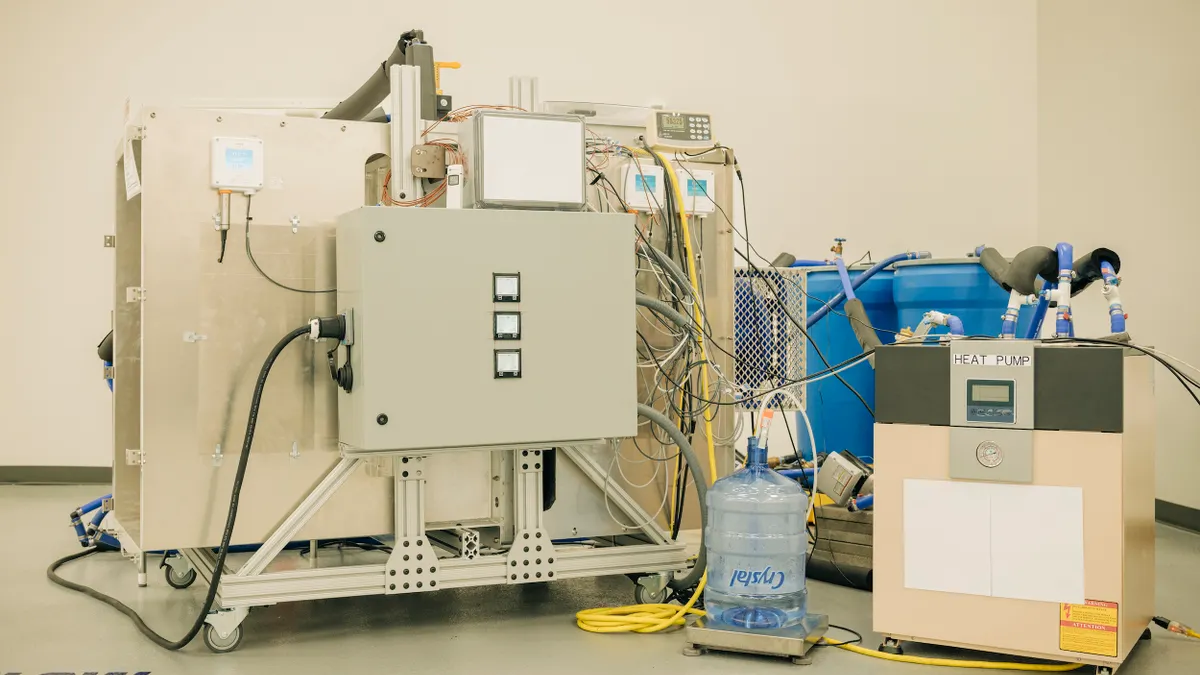

Today, Smart Lake Erie uses various sensors on buoys to monitor nutrients and water chemistry, as well as the weather on the lake and the surrounding area. Herzog said the initiative has various projects related to it, including Smart Citizen Science, which brings next-generation water quality monitoring devices to volunteer monitoring programs in the Lake Erie region and puts them on a common data platform.

Smart Lake Erie plans to launch the first scaled pilot of a high-frequency watershed water quality sensing program this summer in partnership with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and consulting firm Limnotech. That project will focus on showing how lower cost, higher frequency monitoring can collect high-resolution data without sacrificing quality.

"To really see the reductions in nutrients that we need to see in order for our region to really clean up from an ecological perspective, we need to be able to monitor and assess the impacts of various projects that are meant to reduce that nutrient pollution and gather the data to adaptively manage those projects to improve their efficiency and maintain their efficiency," Herzog said.

Results and opportunities

Smart lake projects are yielding results, as well as opportunities in monitoring the conditions of Lakes George and Erie. Kolar said RPI's team of researchers have used data gleaned on Lake George in peer-reviewed papers, including on how changing water chemistry can affect frogs.

The data collected by IBM's myriad IoT sensors feeds into what Kolar called the Jefferson Project's "modeling system," which uses that data to predict the weather and runoff in the entire lake’s watershed. IBM uses its advanced Deep Thunder software to crunch numbers and make those high-resolution weather predictions.

"It enhances the science in that we're intelligently looking at the data, analyzing the modeling data, which is also validated from the sensors, so you have the accuracy well understood, the skill of the model, and from there we can make very good predictions and then react appropriately," Kolar said.

Meanwhile, members of the public can text some of the smart buoys to receive information on the weather, as well as water quality and chemistry. The Jefferson Project has made similar information on weather and water quality publicly available through a digital data dashboard, which it will continue to update over the coming months.

Herzog noted that as problems like harmful algal blooms and salt runoff are solved and the water quality is preserved, it will reduce the costs that drinking water treatment facilities have to shoulder for remediation work.

"In a lot of cases the technologies already exist, it's a matter of figuring out how can we get them implemented properly and how can we sustain the deployment and maintenance of those technologies, and continue to manage it in an iterative and dynamic way."

Max Herzog

Program manager, Cleveland Water Alliance

Less tech-driven advances can also play a role. Reforestation and wetland restoration can help with issues such as nitrogen runoff and reducing nutrients in water systems, the interagency federal report said, though it did emphasize that the use of technology for monitoring and collecting data is key for understanding connections between certain conditions and wildlife impacts.

Modeling can also be crucial in identifying where and when harmful algal blooms may occur, giving local officials an opportunity to stop them before they get too pronounced, according to the report.

As local governments look to replicate what has been done at Lake George and Lake Erie, Herzog recommends a regional approach that involves every government or entity with a stake in the lake's wellbeing. Regional collaboration around smart climate or transportation projects has occurred in the Greater Phoenix and North Texas areas, and Herzog said that type of approach can work for smart lakes, too.

"In a lot of cases the technologies already exist, it's a matter of figuring out how can we get them implemented properly and how can we sustain the deployment and maintenance of those technologies, and continue to manage it in an iterative and dynamic way," he said. "That really requires full-scale and deep collaboration with all the stakeholders and buy-in at a number of levels."

Siy said he hopes Lake George and the Jefferson Project can show others what is possible, especially when the issues are uncovered.

"People need inspiration more than ever and what better place than Lake George to be the font of inspiration for others," he said.